I recently learned that the Ronald McDonald House at the children’s hospital in Indianapolis where I work as a pediatric physician has banned donations of casseroles and other home-cooked dishes. Using capital letters for emphasis, its policy ordains that “ALL food must be prepared in our kitchen or in a commercial kitchen.”

Like all doctors, I get that there’s a good reason for this policy: It is important to protect families and their sick kids from food-borne illnesses. But I also lament seeing limits placed on a great American institution.

Ronald McDonald Houses

Ronald McDonald Houses are charities – backed by funding from the burger chain, its customers and other sources – that give families with hospitalized children a free place to stay nearby. There are more than 350 of them operating in at least 40 countries. These nonprofits also aim to serve such families at least one free meal a day.

Restrictions on homemade fare like those at Ronald McDonald Houses can reduce the number of casseroles provided to families in need.

The concerns are valid. What if any of those casseroles contained some spoiled chicken, were inadequately cooked or sat for too long before landing on the table? Innocent mistakes like these can cause bodily harm and open the door to lawsuits. Faced with such liabilities, any organization might feel compelled to ban homemade food.

Casseroles in America

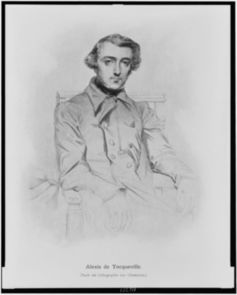

Alexis de Tocqueville’s masterpiece, “Democracy in America,” originally came out in 1835, around the same time that Lettice Bryan published a recipe for “Mutton Casserolles” in her cookbook, “The Kentucky Housewife.”

Whether or not he sampled that nutmeg-seasoned baked dish composed of mashed potatoes, tomatoes, mutton, ham, gravy and wine or any other American casserole, Tocqueville would have recognized it. The word itself comes from the French term for a large deep dish for cooking or serving this kind of food.

More importantly, perhaps, he would have understood what casseroles mean in our society.

Americans gain the love and respect of their neighbors, the French diplomat and historian wrote,

“By a long series of small services, hidden deeds of goodness, a persistent habit of kindness, and an established reputation of selflessness … I have seen Americans making great and sincere sacrifices for the key common good, and a hundred times I have noticed that when needs be, they almost always give each other faithful support.”

I have long believed that America is a nation built on casseroles. During my earliest days as a youth growing up in Indiana and having lived mainly in the Midwest, I have observed casseroles serving as both cause and effect of the ties that bind neighbors together. When someone dies or goes into the hospital, when a baby is born or even when someone moves into a neighborhood, the comforting aroma of macaroni, chicken and tuna casseroles begins to fill the house.

They can pile in like presents at a kid’s birthday party.

Why (all) casseroles matter

The appearance of homemade casseroles on the doorstep does more than relieve the burden of meal preparation. It says that people know what is happening in your life and care enough to help in a way that no gift card, TV dinner or handwritten note can equal. The ingredients may match what’s in a store-bought meal, but homemade hot dishes – as Minnesotans call them – offer a special comfort that not even the best restaurants can provide.

Banning homemade casseroles is a classic example of our tendency to allow lower things to trump higher things and getting our priorities upside down. It reminds me of my youth, when prepackaged candies replaced pieces of fruit at Halloween, supposedly justified by instances of trick-or-treaters who had been injured by razor blades, needles and broken glass – tales that turned out to be greatly exaggerated if not false.

Just as Americans were not sadistically injuring kids, I think we can safely assume that most of us can be trusted to exercise precautions while making homemade casseroles for distressed families.

These dishes are more than a jumble of carbohydrates, proteins, fiber and fats. They are among the most commonplace yet compelling indications that Americans care for each other.

![]()

Richard Gunderman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.