With members of Congress spending the month of August in their home districts, Republican efforts to do away with President Obama’s signature legislative achievement, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), appear stalled, at least temporarily.

However, the Trump administration still appears committed to unraveling the ACA. Most prominent are the threats to withhold cost-sharing reductions, which reduce out-of-pocket payments for low-income consumers on the insurance marketplaces. According to the Congressional Budget Office, cutting these payments would drive up health insurance premiums by 20 percent while costing the federal government close to US$200 billion over a decade.

Ultimately, the future of the ACA remains murky at best, leaving blue states scrambling for alternatives. One of progressives’ favorite solutions was floated by the California legislature at the height of Republican efforts to repeal the ACA: a plan to develop a single-payer health insurance system. Enthusiastic progressives, reeling from a series of defeats since the election of President Trump, quickly hailed the efforts as a path forward in Trump’s America.

Policy experts like me were not surprised when efforts in California petered out, not the least due to the massive price tag of $400 billion annually. Californians had been subjected to similar experiences over the decades, going back to the 1910s. Time and time again, efforts at comprehensive health reform have failed in the Golden State and elsewhere, such as Washington and Kentucky.

To the dismay of progressives, future efforts are likely equally doomed to failure. While states have been innovators with regards to many policies, fiscal issues and regulatory limitations will most likely preclude states from pursuing sweeping health reform. Here is why.

Financing health reform is challenging

Providing insurance to those who cannot afford it is a costly endeavor, particularly in the United States. Without the financial support from the ACA, which currently provides subsidies in the individual marketplaces and pays for well over 90 percent of the Medicaid expansions, states would be required to allocate funds for this purpose. This would be undeniably challenging.

For one, many states are still recovering from the Great Recession. Moreover, other important state functions like K-12 and higher education and criminal justice are taking up large parts of states’ budgets.

Perhaps most crucially, unlike the federal government, states are generally not allowed to carry a deficit so budgets need to be balanced in any given year.

This leaves tax increases as the only solution for states seeking to get more of their residents insured. From an institutional perspective, increasing taxes is a significant obstacle because in most cases this would require a supermajority of the legislature, as well as a willing governor to accomplish. With Republicans by and large unwilling to go this route, this seems exceedingly unlikely in the foreseeable future.

Yet even for those states finding a path to increasing taxes, significant obstacles remain. Unlike for health reform at the federal level, residents and businesses have a degree of mobility that allows them to select their location of residency. So increasing state taxes to fund health care expansion could prompt businesses and individuals to locate to other states with lower taxes.

It would likely also mean that poorer and sicker individuals seeking access to health coverage, particularly from neighboring states, would relocate to these states.

Over time, health reform would thus be financially unsustainable.

Health reform in a federal system is complex

Finances aside, there are also significant intergovernmental regulatory realities preventing states from moving forward on health reform on their own. Two issues stand out.

For one, a little-known law called the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, commonly referred to as ERISA, poses the most crucial obstacle. While mostly intended to address retirement and pensions, ERISA also preempts states from regulating companies that choose to self-insure with regard to health care.

Self-insurance refers to arrangements where companies, instead of relying on insurance company like Blue Cross or Cigna, pay their employees’ medical claims directly. While companies generally contract for the administration of these arrangements, the employing company bears the entire risk. A striking 50 million employees, particularly in large companies, are subject to these arrangements.

Second, states also do not have full regulatory authority over individuals obtaining coverage through Medicaid and Medicare. States are virtually excluded from regulation for the latter and require the cooperation of the federal government for the former.

Combined, this puts more than 50 percent of insurance markets out of reach for state-based health reform efforts, making it inherently unviable.

So how did Massachusetts do it?

Given these limitations, how was Massachusetts able to implement state-based health reform? It took a confluence of fortuitous circumstances.

First, there was bipartisan cooperation at both the state and federal level.

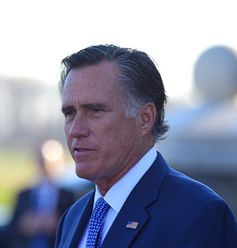

Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, President George Bush and Secretary of Health and Human Services Mike Leavitt, all Republicans, were able to come to an agreement with Sen. Ted Kennedy (Democrat of Masachusetts) and Democrats in the state legislature.

Bipartisanship also meant that everyone was invested in the project, at the state and federal level, and sought to make a success.

Second, the federal government was willing to foot most of the bill and provided regulatory support for the state’s effort.

Third, Massachusetts is a relatively wealthy state that already covered a large percentage of its population.

A confluence like this appears highly unlikely under current political realities.

Moving forward with GOP health reform

States have a long history of developing sound policy solutions. For example, Wisconsin pioneered both unemployment insurance and pension schemes that laid the foundation for federal policies during the New Deal.

Yet states are not equally well-equipped to address all policy issues. Comprehensive health reform is one of those issues.

Current GOP proposals would do little to overcome the financial and regulatory barriers to state-based reform.

Indeed, states would be further inhibited by significant cuts to the Medicaid program. Moreover, waivers included in the various proposal, in a marked contrast to the ACA, are focused on allowing states to provide less coverage and fewer benefits.

Allowing policies to be sold across state lines, if successful, would further restrict the sovereignty of states to regulate their insurance markets.

Republican efforts to repeal and potentially replace the ACA may not be dormant for long. The Democratic victory in the Senate in July was a shaky one that could be quickly undone, for example, if Sen. Joe Manchin (Democrat of West Virginia) or Sen. John McCain (Republican of Arizona) choose to leave the Senate. The 2018 election for the Senate also puts Democrats at a significant disadvantage and Republicans may further enlarge their majority.

Unquestionably, progressive legislators will continue to introduce bills aimed at comprehensive reforms. Yet, history and economics tell us that these efforts are unlikely to make much headway. The structural limitations of states in a federal system may confine their efforts to filling in the gaps until the federal government further extends coverage.

![]()

Simon Haeder does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.